Jordan Expedition

The Khirbat Iskandar Excavations: Nine Major Excavation Seasons

The overall project director since 1981 has been Gannon University professor Suzanne Richard, Ph.D. There have been 13 seasons of field excavation, research, and restoration work at the site of Khirbat Iskandar: full field excavations took place in 1982, 1984, 1987, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2010, 2013, and 2016; with an upcoming season in 2019 planned. There were also two pilot seasons: a 1981 season of survey and soundings, and a 1994 season of study and exploration, and restoration and preservation seasons in 1998, 2006 and 2008. Restoration and preservation are major components of each excavation season.

The project from the beginning has been approved by the Committee on Archaeological Policy (CAP) and affiliated with the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR). The project works closely with the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) in Amman, Jordan and operates under the guidance and by permit of the Department of Antiquities of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Currently, the project is sponsored by a consortium of three universities: Gannon University, Lubbock Christian University and McMurry University. Jesse C. Long, Jr., Ph.D. of Lubbock Christian University became a co-director in 1994; Professor Bill Libby from McMurry University has been a long-time contributor and director of the consortium since 1997. Marta D'Andrea, PhD, from Sapienza University of Rome joined the team in 2016 as co-director as well.

Earlier excavation of the site took place in 1955, when Peter Parr of the British Institute in London excavated two trenches. Prior to that, Nelson Glueck explored the site and reported on it in his monumental work, Explorations in Eastern Palestine, 1939. He was the first to recognize the importance of Khirbat Iskandar for Early Bronze Age studies, especially the EB IV period. Most of the well-known explorers, travelers, architects of the 19th century visited Khirbat Iskandar and discuss the site in their writings.

The following photos show some of the great team members over the past several seasons: 2016, 2013, and 2010.

2010 Team

Historical Background

Khirbat Iskandar is an Arabic name and means the "ruin of Alexander (the Great)." This name is taken from a modern village nearby; the original name of the site is unknown. The name is what archaeologists would call anachronistic, since Khirbat Iskandar is an Early Bronze Age site and Alexander the Great lived and conquered the area thousands of years later (323 BCE). The Early Bronze Age (EBA) dates to ca. 3700 - 1930 BCE, a long era that saw the rise and collapse of the first cities. It is subdivided into four periods: EB I from 3700-3100; EB II from 3100-2900; EB III from 2900-2500; EB IV from 2500-1930. Not that these dates reflect recent research (carbon 14 dating and Bayesian modeling) that raised the dates for the EBA by several hundred years. This move impacts the site of Khirbat Iskandar and its EB III-IV phasing especially. Now the EB IV period is almost 600 years long with important historical, interregional and international consequences (see below).

Khirbat Iskandar is an Arabic name and means the "ruin of Alexander (the Great)." This name is taken from a modern village nearby; the original name of the site is unknown. The name is what archaeologists would call anachronistic, since Khirbat Iskandar is an Early Bronze Age site and Alexander the Great lived and conquered the area thousands of years later (323 BCE). The Early Bronze Age (EBA) dates to ca. 3700 - 1930 BCE, a long era that saw the rise and collapse of the first cities. It is subdivided into four periods: EB I from 3700-3100; EB II from 3100-2900; EB III from 2900-2500; EB IV from 2500-1930. Not that these dates reflect recent research (carbon 14 dating and Bayesian modeling) that raised the dates for the EBA by several hundred years. This move impacts the site of Khirbat Iskandar and its EB III-IV phasing especially. Now the EB IV period is almost 600 years long with important historical, interregional and international consequences (see below).

The Early Bronze Age was a momentous period in the history of humankind. Why? Because it is the period of the first cities and the dawn of history: the time when writing was discovered. These great discoveries occurred in Mesopotamia and in Egypt. The "biblical lands" (the southern Levant) were greatly influenced by these advanced urban cultures to the north and south. Thus cities soon arose in Israel and Jordan as well, although evidence of writing is not found until the Middle Bronze Age, after 2000 BCE. The Early Bronze Age people are often called Canaanites" and/or "Amorites" given the evidence for successive Bronze Age continuity when the country and its diverse ethnic population are attested. The Bible also indicates that the Canaanites occupied the and before the Israelite, who are first mentioned in the Merneptah stele, ca. 1207 BCE. However, recent aDNA evidence complicates the issue with data showing that northern populations were in the country in the 4th and 3rd millennia, i.e., probably from the Caucasus area.

The Early Bronze Age in the Near East is a period that can be distinguished from earlier times by a "leap" to cultural complexity. When people began to build cities, a great step occurred in human civilization. It is the very foundation of our own society today. The transition from hunter/gatherer to farmer was the first step in the development of settled life and it occurred much earlier (ca. 12,000-10,000 BCE). It was a long and gradual process, but as time went on life became more and more complex and the origin of cities was the result. There are many reasons why people would want or need to live in cities. As part of its research design, the Khirbt Iskandar project is exploring the development of greater complexity that led to cities and is asking why cities suddenly disappear, as happened at the end of the EB III period in the southern Levant.

Significance of Khirbat Iskandar for the Early Bronze IV Period

Khirbat Iskandar is often called the most important site in the EB IV period. It is because it appears to have urban-like features reminiscent of the preceding urban EB III period. One of the trademarks of a city is usually its fortifications, and in EB IV (known as a "pastoral-nomadic" period) Khirbat Iskandar reused and partially rebuilt the earlier fortifications. Once unique at the site, fortifications now have come to light at a half a dozen sites with more known from survey. Along with a gateway, the site boasts a public building comprising a storeroom and a cultic area, among many other "urban-like" traits. Khirbat Iskandar evinces strong evidence for continuity of "tell" settlement following the destruction/abandonment of most EB III sites. It is not unique--there are more and more "tell" sites yielding evidence for the EB IV. Nevertheless, the period does see the founding of many new sites away from the destroyed "tells." Many of the latter likewise exhibit continuity with antecedent EB III traditions. Along with continuity there is change, renewal, and development.

In the past, the hybrid-like character of the culture (EBA traditions/new influences from Syria) led to theories of nomadic invaders from the North descending on the souther Levant following the demise of urban sites. Some reasons for the latter were reflected in the "caliciform" (cup) ceramic culture disseminating from Syria along with some new metal and tomb types. Knowing today vastly more about the Early Bronze Age in both Syria (northern Levant) and the southern Levant (Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories), it now seems likely that a combination of factors is more explanatory--indigenous continuity, some migrating peoples from the north, the unremitting spread and diffusion of the dominating cultural attributes of neighboring societies in Syria and Egypt, the dissemination of ideas, interconnectivity etc.

In comparison with the monumental cities of EB II-III, the EB IV settlement at Khirbat Iskandar was probably more of a town or regional center. The EB IV period is generally described as a "Dark Age" or a  "Nomadic Interlude." That's because until recently mostly cemeteries had been excavated and not much was known about the culture. It soon became clear, however, that much of the population was sedentary and living permanently at new or or "tell" sites. Indeed Nelson Glueck, the famous archaeologist and explorer of Transjordan in the early 20th century, described Khirbat Iskandar as a fortified EB IV site having an upper and lower mound.

"Nomadic Interlude." That's because until recently mostly cemeteries had been excavated and not much was known about the culture. It soon became clear, however, that much of the population was sedentary and living permanently at new or or "tell" sites. Indeed Nelson Glueck, the famous archaeologist and explorer of Transjordan in the early 20th century, described Khirbat Iskandar as a fortified EB IV site having an upper and lower mound.

Thanks to greater exploration, excavation, and survey over the past 20 years, our views on the EB IV have changed quite a bit, on the EB III period as well. If we consider the new chronology (mentioned above) it is now necessary to shift the synchronisms between the southern Levant vis-à-vis Egypt and Syria. Previously, the EB III urban period was thought to align with the Egyptian Old Kingdom (4th-6th dynasties). In the new chronology, however, the EB III period now is coeval with the Dynastic Period (dynasties 1-3) and the fiRst half of the 4th dynasty (the latter being the "Pyramid Age"). As amazing as it may sound, the so-called "pastoral-nomadic" period (EB IV), now dated to 2500-1930 BCE synchronizes with the Old Kingdom Period, as well as the Intermediate Period near the end of the millennium. The ramifications of this synchronism remain to be sorted out, as scholars today reevaluate the third millennium CE in the southern Levant. Some of the publications found on this web site detail the evaluation of the P.I. of Khirbat Iskandar, Dr. Suzanne Richard.

Location and Description

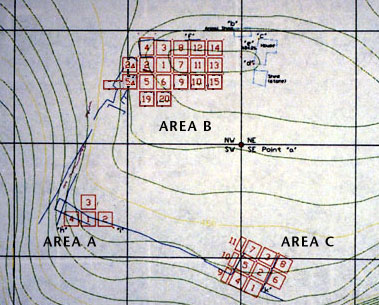

Look at the accompanying map to find Khirbat Iskandar. As you can see, it is east of the Dead Sea and south of Madaba, a major town about 30 miles south of the capital city of Amman, Jordan. It takes about an hour to drive from Amman to Khirbat Iskandar; from Madaba to Khirbat Iskandar is approximately 25 minutes by bus. The site sits on the north bank of the Wadi el Wala, at an important crossing point of a famous caravan route called the "King's Highway." The ancient inhabitants probably chose its location also because the wadi was a perennial river and an important source of water at that time; there is still water in the wadi today.

Defense is always a consideration and so the city was built on a hill, which is why it is called Khirbat Iskandar and not Tell Iskander. Over 1500 years, the mound (which is 20 meters/65 feet above the surface level) rose steadily as successive cities and settlements were built, destroyed, and rebuilt. The mound gradually began to look more like a tell. This buildup occurred because, unlike today, there were no bulldozers to clear the destroyed city before a new one was built. At an overall size of about 8 acres, Khirbat Iskandar is generally in the range of a medium-sized site, although as indicated elsewhere, the great site spread further across the landscape than just the tell, making it highly likely that the site was more like 15 acres. Besides the cemeteries, megaliths, and high place, Nelson Glueck found occupation beyond the site, e.g. a menhir stood across the wadi to the south, and occupational remains were noted to the north and east of the site as well.

What have we learned about the inhabitants of Khirbat Iskandar over the years?

a) The Area C Gateway

![/uploadedImages/Website_Assets/History_and_Archaeology_Department/Archaeology/ruins2[1].jpg /uploadedImages/Website_Assets/History_and_Archaeology_Department/Archaeology/ruins2[1].jpg](/uploadedImages/Website_Assets/History_and_Archaeology_Department/Archaeology/thumb_ruins2[1].jpg)

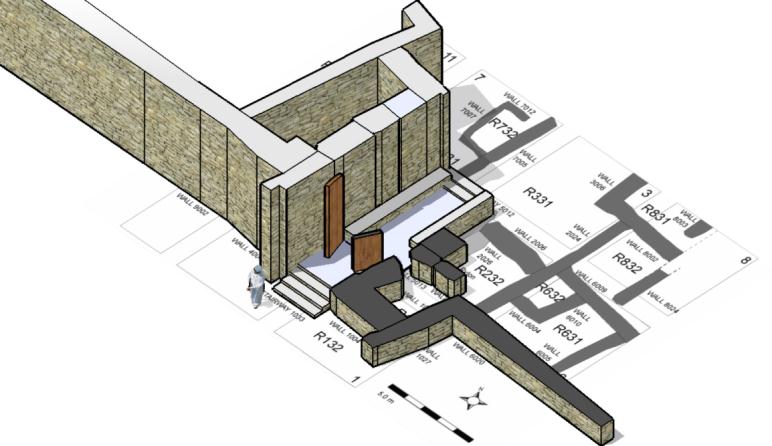

Although work in Area C came to an end with some minor exploration in 2007, given the importance of Khirbat Iskandar's three phases of settlement in the EB IV, along with an apparent EB III-IV transitional phase, the project decided to return to Area C in 2016. Excavation had ended in 2007 so that restoration on the only "gateway" in the EB IV period could move forward with a view toward preparing the area for tourism. The final report on Area C was published by the American Schools of Oriental Research in 2010. See a link to the publication page for Vol. 1 of the Khirbat Iskandar Expedition Series: the EB IV Area C Gateway and Cemeteries. The team returned to the area in order to recheck the phasing and the ceramic sequence derived from a quantitative study that revealed high probability of changes in pottery types over the three phases discovered through excavation. The results have provided additional exposure of the "work area" at the east end of the area (Squares C6 and C8). As the photo shows, the three phases uncovered previously have greater horizontal exposure as the Phase 1 and 2 structures continue northward into Square C8; the Phase 2 structure is clearly evident in the photo. Moreover in Phase 3 the room of C8 was totally exposed, now clarifying a massive square stone as the center pillar base. It was once considered to possibly be a work table. Although the intent was to clarify Phase 1 and the relationship to earlier phasing, the short season only allowed the excavators to clarify Phases 2-3 and to discern a mudbrick layer below Phase 1, undoubtedly the same EB III destruction layer found throughout the site.

As mentioned, and as photo 2 shows, Area C is significant not only for being a nique gateway into the town, but also for its three superimposed stratigraphic phases. The figure above shows the relationship of three walls, one above the other, over three phases. Phase 1 is extremely important for its domestic remains as well as its pottery, which appeared to be transitional EB III/EB IV. The assessment was that it represented a period of recovery following the destruction of the site in EB III. Phase 2, a settlement showing a well-built and characteristic eBA traditional broad-room house and a courtyard, appeared to be more prosperous. In Phase 3 segments of the earlier structures and rebuilding resulted in the reconfiguration of the area into a two-phase "gateway." This is the best-known phase and in the isometric drawing, the later phase is visible although blockages in the walls juxtaposing the walkway are apparent. You can see steps at the lower and at the upper end of the plastered passageway. The passageway is lined with stone benches. It seems that people entered the gate in order to walk to the upper part of the mound. We don’t really know what activities went on in this gateway, but literary references are suggestive. The Bible mentions that “justice took place in the gate." Other ancient Near Eastern texts refer to trade and other types of activities.

On either side of the entryway are large structures that perhaps were"guardrooms," one of which was paved. The remains found to the north of the upper steps indicate that the area was a courtyard. Off to the left of the courtyard, there is a  small room, which appeared to be a storage area and per has cooking area, for there were storage jars sitting on the pavement at one end. To the right of the gateway were work areas. We drew this conclusion based on features such as work tables and the large stone table and “benches” that were found in association with a great amount of flint debit age, along with ground stone objects for pounding and shaping flint cores into actual knives, and other types of tools. The architect's vision of what the gate may have looed like (fig. ) helps us to visualize the important entryway the inhabitants would enter in order to reach the upper area.

small room, which appeared to be a storage area and per has cooking area, for there were storage jars sitting on the pavement at one end. To the right of the gateway were work areas. We drew this conclusion based on features such as work tables and the large stone table and “benches” that were found in association with a great amount of flint debit age, along with ground stone objects for pounding and shaping flint cores into actual knives, and other types of tools. The architect's vision of what the gate may have looed like (fig. ) helps us to visualize the important entryway the inhabitants would enter in order to reach the upper area.

The photo of the flint knives shows a perfect example of what is known as a "Canaanean blade." It is worked on both sides. A number of these blades were placed inside a scythe or sickle tool, which was used to cut grain. Archaeologists know this because the blades usually have a patina or glossiness from contact with grains.

b) Early Bronze IV: the Phase B, Area A Settlement

A very different kind of neighborhood came to light in the latest phase (A) in Area B. There we found a lot of evidence for the everyday life of people who must have walked through the gate in order to reach their homes at the northwest corner. Most of the buildings were strung together, that is they shared one or two walls with neighboring houses. Looking at the plan, we can see that the buildings could be "long-room" or "broad-room" houses. The structure in B1 is long, since as you enter, you see the length of the room; whereas, the doorway in B10 is on the long wall so that when you enter, the room appears to be broad, not long. Note that unlike B1, many of the buildings are subdivided into several rooms.

We may assume that, as in our very own homes, they had kitchens, sleeping rooms, work areas. Because the archaeologist saves everything during the excavation, it is possible to study the associations of materials, which aid in discerning particular types of activity areas. For example, there was cooking activity found in B1, B2, B7, and B19 since excavation uncovered a tabun in each of those areas. The best associations of materials were found in B19. Near the tabun was a mortar used for grinding grain to make flour probably, and a large flat slab nearby probably served as a preparation surface for making the bread. Also in this room was a small bin, where

.jpg)

vessels containing food and liquids were probably stored. We are calling this activity area a kitchen. Additional excavation of this house revealed a building with multiple rooms, including an apparent domestic cultic room, as suggested by the two pillars.

vessels containing food and liquids were probably stored. We are calling this activity area a kitchen. Additional excavation of this house revealed a building with multiple rooms, including an apparent domestic cultic room, as suggested by the two pillars.

Further evidence for activities appeared in B11. This house, apparently, was used for a different type of work than the preparation of food. Here we found a table with a small depression next to a mortar set into the ground, as well as a large stone slab or table. These seem to be grinding installations. In the room a great deal of red powdery material was found in the surface, indicating that perhaps hematite or another material was being ground up and used as a coloring agent.

Note also that this house and the house next door both had a row of pillars. Since pillars were not found in other houses, it is clear that they signify a different activity, perhaps status or wealth of the owner. It may reflect a type of courtyard house, where one half of the building was covered and the other open. In later periods, we know that small farm animals like sheep and goats might be stabled under the roofed section, while domestic activities took place in the courtyard and the people lived in another room or on a second floor.

A few other different types of activities are indicated; for example, in B2 there is a series of small bins dividing the space. It is difficult to know if they are for small animals or for work areas. There is a large courtyard in B5.

Over all, in Phase A we have what appeared to have been a typical Early Bronze Age permanently settled community of people who were farmers, who, like farmers today own flocks of animals as well. It seems that the community was fairly self-sufficient, since evidence for various types of manufacturing processes was discovered. Although a potter's kiln has not yet been found, studies of the clays used in making the Khirbat Iskandar pottery suggest that the pottery was made locally.

In short, in a period when there is less complexity and fewer interrelations among sites, the people of a community have to do everything in order to survive. In the EB II-III, on the other hand, certain towns and cities would provide specialized objects for trade, the smaller farming communities would produce the grain for the cities, and pastoral-nomads would tend large flocks in order to trade meat and dairy products with the cities. The Phase A community at Khirbat Iskandar reflects the end of a 1500 year long civilization. Although there is clear evidence for continuity of populations into the Middle Bronze Age at ca. 2000 BCE, new ideas, peoples, and cultures will bring in the vibrant new urbanism of the Middle Bronze Age era.

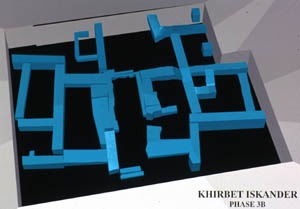

c) Early Bronze IVB, Area B, Phase B Settlement

Digging into earlier layers of the EB IV period has shown us that prior to Phase A, the community was more sophisticated, more complex, and more diverse. How do we know this? Well, this settlement was enclosed by a strong defensive wall. In Area B, rather than a series of domestic structures oriented north-south, we found a large public complex, that is, a number of rooms that all seemed to be part of one structure. The rooms utilize the fortifications as their back wall, so it's much different from the last settlement (Phase A) above. .jpg)

There is a large central room that has pillar bases. There would have been wooden beams set on them holding up the roof. We know this because we found the remains of the beams. In the corner was an exceptionally well-made stone slab-lined basin. It contained many layers of seeds, grains, olives, and other remains. Through a doorway, one entered the bench-lined room next door to the left. There were many vessels in both the central room and the bench room, some found upside down in destruction debris.  Remains of foods were found in some of the store jars. An entrance with steps was found in the main room. There was a pivot stone which indicates there was a doorway.

Remains of foods were found in some of the store jars. An entrance with steps was found in the main room. There was a pivot stone which indicates there was a doorway.  The steps led south into a corridor and presumably into other rooms of the building. Further excavation has now clarified the area to the south somewhat. We now know that there were a series of rooms and courtyard associated with the storeroom. We are in the process of linking up the rooms to the west also so that we will have an overview of the entire Phase B settlement. Off to the west, a second complex has appeared, including another well made stone slab bin, elongated in shape, near which two votive cups were found.

The steps led south into a corridor and presumably into other rooms of the building. Further excavation has now clarified the area to the south somewhat. We now know that there were a series of rooms and courtyard associated with the storeroom. We are in the process of linking up the rooms to the west also so that we will have an overview of the entire Phase B settlement. Off to the west, a second complex has appeared, including another well made stone slab bin, elongated in shape, near which two votive cups were found.

This structure is extremely important because most of the vessels on display at the Archaeology Museum Gallery at Gannon were found in it. It is unlikely that a family would have over a hundred vessels in their house. This is why we think that this is a public building of some sort. It may have been a storeroom for the entire town. It may indicate that there were leaders or elites of the community who controlled the food and distributed it to the people.

It is also possible that there was a religious or cultic function or purpose to this structure, since many unusual things were found. For example, numerous miniature vessels were found near the stone basin. Often miniatures are used for libation purposes, that is the pouring of sacred liquids. Also, one area included a stone-lined pit in which we found a beautiful bowl that had in it the hoof of a bovine, perhaps the remnant of an offering. Nearby were goat horns, often an indicator of the cult. In a context with the stone-lined bin, in which there were many levels of foodstuffs delineated (perhaps offerings), it is reasonable to infer some type of cultic activity.

.jpg)

Thus, as we prepare Area B for publication in Vol. 2, our working hypothesis is that the public complex and its numerous unique features is not a domestic structure but rather provides striking evidence for elites living and ruling at the site, and whose storerooms indicate either a cultic area, a redistribution center, or surpluses of food, liquids, and oils used for trade.

This complex reflects a type of activity different from the later Phase A domestic houses found above. In Phase B we have not found tabuns for example, or much evidence for a variety of occupations and work in this area. The conclusion is that the population was more specialized and included different occupational areas across the mound.

All of this seems to show that, at the beginning the EB IV, inhabitants continued the ways of the urban EB III peoples. Only toward the end, Phase A, did they drift into more of a village-type economy.

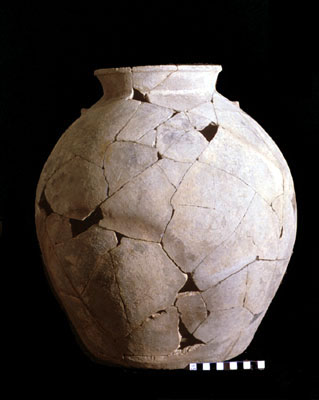

Earlier urban Settlements at the Site--Phases C, D, E

There may have been a transitional phase between the EB III and the EB IV Phase B settlements, although we are not yet certain. The destruction layer covering the Phase C (EB III) settlement was significant, followed by the rebuilding activities of the EB IV occupants. The major stratum below (Phase C) is a settlement for which there is evidence of two phases. We know the most about the settlement that was destroyed, thanks to the aterials found in place below a thick level of destruction. What is clear is that the original Phase C people built very different structures that comprised a stone base and mudbrick superstructure. Some of the walls are still standing to 6' high. The photo gives a view of a central room with pillar base; the room is built right up against the fortifications. It is in this room where much of the pottery, many storejars filled with lentils, was found within destruction debris of roofing stone, mudbrick, beams and ash. At the west end, there is a well-preserved wall with doorway and stone threshhold. Its surface led to steps that a person could use to climb to the top f the tower to guard for enemies approaching the site.

There may have been a transitional phase between the EB III and the EB IV Phase B settlements, although we are not yet certain. The destruction layer covering the Phase C (EB III) settlement was significant, followed by the rebuilding activities of the EB IV occupants. The major stratum below (Phase C) is a settlement for which there is evidence of two phases. We know the most about the settlement that was destroyed, thanks to the aterials found in place below a thick level of destruction. What is clear is that the original Phase C people built very different structures that comprised a stone base and mudbrick superstructure. Some of the walls are still standing to 6' high. The photo gives a view of a central room with pillar base; the room is built right up against the fortifications. It is in this room where much of the pottery, many storejars filled with lentils, was found within destruction debris of roofing stone, mudbrick, beams and ash. At the west end, there is a well-preserved wall with doorway and stone threshhold. Its surface led to steps that a person could use to climb to the top f the tower to guard for enemies approaching the site.

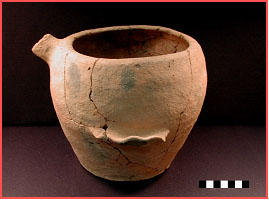

To the south of this large room, there was a courtyard, attested by a well-made stone bone and a mortar. Interestingly, two post holes were found as well. Another room was found west of the courtyard in which a host of unusually well-made stone bowls were found, along with a potter's wheel, a macehead, and much restorable pottery as seen by the "teapot" shown in the photo. We continue to expose more of the Phase C settlement, as well as earlier occupation along the western perimeter of the site.![/uploadedImages/Website_Assets/History_and_Archaeology_Department/Archaeology/b040527[1].jpg /uploadedImages/Website_Assets/History_and_Archaeology_Department/Archaeology/b040527[1].jpg](/uploadedImages/Website_Assets/History_and_Archaeology_Department/Archaeology/thumb_b040527[1].jpg)

The fortifications at Khirbat Iskandar comprise two major wall lines, a square tower, a platform, and transverse walls. As we now understand, the Phase C fortifications, tower, and platform were a secondary reinforcement of an earlier (Phase D) inner mudbrick wall with towers that suffered major destruction as well. Although this was our hypothesis early on, the recent discovery of a curved mudbrick wall running under the tower dispels the questions we originally had concerning the relationship of the mudbrick to the outer stone defenses. The combined fortifications in Phase C then range as thick as 8’ near the highly fortified northwest corner. More recent excavations have revealed that two curved mudbrick structures on stone socles, presumably towers, are juxtaposed on either side of a stone threshold, looking very much like an entrance. Other well-built mudbrick walls on stone socles have come to light in Phase D. Our goal in future excavations is to connect the mudbrick structures with interior occupation so as to clarify whether they date to EB II or EB I.

Cemeteries

As mentioned above, there are numerous cemeteries in the vicinity of Khirbat Iskandar.

As mentioned above, there are numerous cemeteries in the vicinity of Khirbat Iskandar.  To the east is cemetery E, to the west is Cemetery J, and across the wadi to the south is cemetery D. Mostly the project has excavated EB IV shaft tombs. In the EB IV period, people did not bury their dead in huge caves as the urban people did, probably indicative of family burials.

To the east is cemetery E, to the west is Cemetery J, and across the wadi to the south is cemetery D. Mostly the project has excavated EB IV shaft tombs. In the EB IV period, people did not bury their dead in huge caves as the urban people did, probably indicative of family burials.

In the chamber of the shaft tomb E6, we found evidence for multiple burials along with pottery and objects. Tomb E3, however, was small and only had a pile of bones around which were four vessels. We have not found any burial evidence for the EB II-III period, although there are a number of robbed caves that we investigated in the hillside across the wadi to the south.

In Cemetery J to the west,one EB I tomb was found. It was very different from either of the two types of burial customs mentioned. This was a cist tomb that was dug into the ground and then covered with stones. In it were many bone fragments and typical EB I pottery like the duck-bill storejar, as well as small cup with high handle, which was used as a dipper juglet for dipping out water.